Trauma Bonding

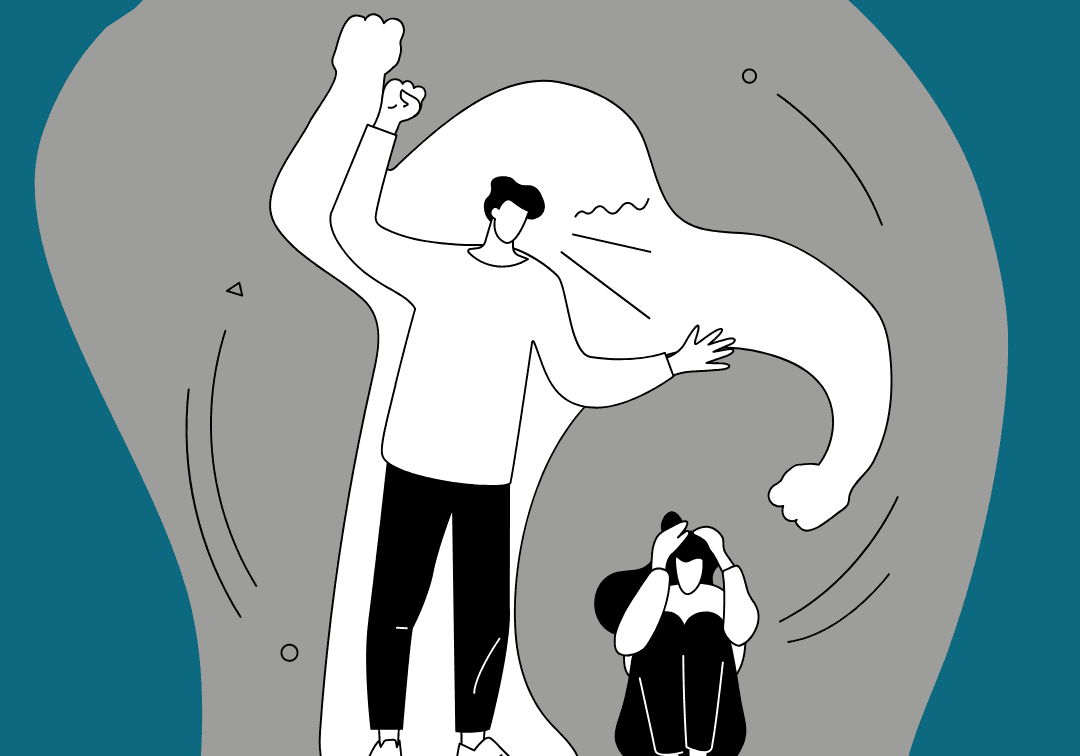

Trauma bonding is a common psychological response to cycles of abuse.

What is Trauma Bonding?

Trauma- bonding is a term that is used to describe the emotional bonds formed with an individual or within a group such as a family or cults where there are cyclical patterns of abuse which are reinforced with patterns of rewards and punishment.

This cycle of emotional and psychological abuse along with other forms of abuse which includes times of relief and positivity forges a trauma bond between the person receiving this inconsistent pattern of reward, punishment, and abuse and the one perpetrating this abuse. This then widens the power imbalance within the relationship.

Trauma-bonding often occurs within romantic relationships and is central to domestic abuse, it also occurs within families between parent and child, abusive sibling, friendships, cults, and human trafficking.

Trauma bonds are forged within intimate relationships and based on fear, control, and the lack of predictability over whether the one with power will be kind or punishing. This lack of consistency around harm leaves room for hope and the sense that if you can be more obedient and make yourself and your needs smaller you will then receive that person’s love and acceptance, making all well and safe. Keeping the other person happy while meeting their expectations and needs becomes the sole focus and your needs become reduced to maintaining the peace by keeping them happy within trauma-bonding.

My experience of trauma bonding

Something that helped me make sense of the childhood trauma-bonding with my mother was when I learned that the amygdala, which is the part of the brain where our survival instincts of fight, flight, freeze, and fawn activate, has two functions. Our amygdala during traumatic events overrides other functions to ensure our survival, but it also has an equally important function in forming and maintaining core attachments. It makes sense that our amygdala forges and maintains attachments with our caregivers, because as infants and children if we don’t attach successfully with our caregivers forming loving bonds, we won’t survive.

The function of attachment within the amygdala also helped me to understand why although my mother’s anger and words wounded me deeply and her choices at times both lead to my neglect and endangerment, she also felt like the rock my sense of self and heart was formed on. I came to believe that her needs were more essential then my own, and reduced my needs to her being the happy well version of herself capable of loving me because when she was ok and happy so was I. However, no matter how hard I tried, I could never be good enough to prevent relational rupture and my mother viewing me as a problematic child. I remember loving my mother deeply as a child for she was my whole world, but also sobbing when alone “if this was love I wanted none of it” it felt so painful and destructive.

Over time I realised that I could never be good enough, obedient enough or make myself and my needs small enough to maintain relational harmony with my mother and prevent feelings that I was unlovable while fearing rejection and abandonment. I wished as a child that I could convince my heart that I didn’t love my mother and she would never love me, then this painful cycle could end. I didn’t understand then that my brain and heart were lying to me, as every time there was conflict with my mother my amygdala would assure me that if she rejected me, it was because I was bad, and I wouldn’t survive her abandonment. I would be desperate to repair the rupture at any cost, taking the blame fully on myself and ending up betraying myself to restore the peace. My mother felt like the protection and safety from other dangers I needed to survive. She also felt like the sunshine that would make me warm and glow when she was pleased with me, while at the same time being the most harmful and dangerous person in my world.

Why don’t they leave?

While each trauma-bonding has its unique dynamics and different risks depending on forms of trauma and abuse involved, I believe that the emotional knots of fear mingled with conditional love are universal. Trauma-bonding is a critical part of all domestic abuse dynamics as when you are in your own space separate from the one harming you it’s easy to have clarity that what is happening isn’t ok and decide that you’re leaving. However as soon as that person comes back knocking on the door, repentant and promising that they love you and will never hurt you again, all those promises to yourself and others fall away. If you ask people why they go back, they will say it’s because they love the other person and the other person has promised to change and they aren’t all bad. While this is part of the truth, this sense of attachment and love also masks the elements of fear involved, both fear of what the other person might do if they don’t get what they want and the fear that they won’t survive if this other person does abandon them.

Healing from trauma bonding

Trauma-bonding is difficult to heal and get free from because you are basically battling warring instincts whenever you’re triggered by the other person. Healing from trauma -bonding is messy and hard. Healing often requires complete separation from the other person and this is essential if they are a currant physical risk to you. However not having the other person in your life can be impossible if they are part of your family, in which case it’s really important to work through with your therapist what level of contact is safe for you and the kind of boundaries needed to prevent you from being triggered into that trauma dynamic where you lose yourself again.

Becoming free from a trauma bond also requires allowing the fantasy of what that other person could be if they were consistently the loving version of themselves to die while accepting the reality that the person you care about is damaging and unlikely to change.

There is a lot of grief in the process of accepting that the love you deserve and sometimes see glimpses of in the other person is never going to be a consistent positive thing from them and that you can’t save the other person or love them enough to transform this broken damaging love into something healthy and unconditional.

If you recognise this dynamic in any of your relationships, know that it is not your fault and be kind to yourself as healing will take time as will grieving the death of the relationship you envisioned having. It is important to get professional support to work through all the tangled attachments and distorted beliefs that form as a result of relationships like these.

Other blogs about the impact of trauma

The latest from our news and blogs

Trans, Non-Binary, and Intersex (TNBI) Support Group

Coming together in a confidential space to support each other and identify ways to move forward after rape & sexual abuse.